- Home

- Marta Moreno Vega

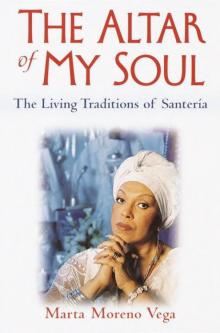

The Altar of My Soul

The Altar of My Soul Read online

More praise for The Altar of My Soul

“A graceful tribute to a timeless religion, a testament to the transformative power of discovering your own spiritual guide.”

—New York Daily Challenge (Brooklyn)

“Highly recommended … Vega elegantly describes the rituals, meaning, and continuing relevance of Santería, weaving her story into 12 chapters, each devoted to a different deity. Vega’s account is rich with patakís (“mythic stories”) and the lessons they teach for daily living.”

—Library Journal

“Engaging, scholarly, and accessible, this is an excellent book.”

—Booklist

“Vega makes an excellent, informed spokesperson on Santería, and her accessible book will help explain Santería beliefs and practices to a wide audience.”

—Publishers Weekly

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1 Olodumare: The Unknown Is the Path to Knowledge

2 Yemayá: No One Knows What Tomorrow Will Bring

3 Obatalá: Power Resides in Cool Heads

4 Ellegua: The Obvious Is Not Always the Correct Answer

5 Ochun: The Goddess of Honey

6 Oyá: In Order to Live You Must Die

7 Shangó: Born to Make War

8 Orula: Guardian of Knowledge

9 Orí: We All Have Our Personal Orisha

10 Ochosi: In Unity There Is Power

11 Orishaoko: Guardian of the Earth

12 Ayáguna: Yo Tengo Mi Aché: On Having Aché

Appendix

Glossary

Acknowledgments

To My Guardian Angels:

There are spirits and people who have the ability to make things happen. They possess an energy force that makes the seemingly impossible a reality. Their aché, the ability to make things happen, flows from them like an invisible shield that encourages and nurtures. It has been my good fortune to have these guardian angels guide me throughout my growth. They have been the ones who helped me see beyond my dreams and make them real.

IN THE SPIRIT WORLD:

I praise the spirits of my parents, Flora Marcano Cruz Moreno and Clemente Moreno. To Abuela Luisa, my uncles Donato and Maximo, enlightenment. I pray for peace for the spirits of my sister Socorro Moreno and brother Alberto Moreno.

IN THE PRESENT:

I celebrate the warrior spirit of Laura Moreno, my ex-sister-in-law, who is my true sister. I ask the spirits to protect her always. She is the main source of strength and stability for our family. Like Yemayá, she is the primordial mother. To my niece Melody, who is so caring, like Ochun, may she continue to spread the honey of her kindness. I honor the creative warrior spirits that protect my sons, Sergio and Omar. I am blessed that these two spirits came through me. I am in constant admiration of how they have bloomed into principled young men. How embracing the boundless energy and soul force of my daughter-in-law Jenna is in my life. I thank Sergio and Jenna for my granddaughter Kiya who continues to expand my heart with love and joy.

I am humbled by my spiritual blessings to have Zenaida Rodríguez and Elpidio Cárdenas as my godparents, mentors, and guides. Their wisdom is endless. Limited space does not allow me to express the love I have for all the members of my family who have been part of my growth and spiritual enlightenment. However, I must at least mention their names so they know they are in my heart: Kilani, Jovan, Eddie, Chino, Norma, Erica, Elisa, Tinesha, Yari, Kadesha, Cudjoe, Djingi, Eula, Laura P., Nyoka, Danetta. Know that you are in my heart and prayers.

TO ANGELS WHO HAVE COME INTO MY LIFE,

THANK YOU:

My agent Joanna Pulcini, of the Linda Chester Literary Agency, like the calm flowing vigilance of the spirit of Yemayá, shares her knowledge selflessly and is always supportive. Joanna’s nurturing spirit is encouraging and insightful. How wonderful to know that the extraordinary talents of both Joanna and Linda Chester are present in my life. To Gary Jaffe and Kelly Smith, who are always at the other end of the telephone helping solve problems, a special hug.

To the overflowing generosity of Cheryl Woodruff, vice president and associate publisher, One World Books of the Ballantine Publishing Group, how wonderful to connect to a spirit force that understands that all nature-based belief systems are inextricably linked into a global sacred circle. It is a joy to share thoughts on ways of connecting the spirits of world cultures. The drawings of Manuel Vega, an artist and Candomblé priest, creatively illustrate the sacred spirits and rites that celebrate the practices of the Lucumí/Santería belief system. A special thanks to Paulo Bispo, Brazilian Candomblé priest from Bahia, for creating the altar for Obatalá and Yemayá at the Caribbean Cultural Center that graces the back cover of the book.

To my guardian orishas, Obatalá Ayaguna and Yemayá, who make all things possible, kimchamaché. To the ultimate energy force Olodumare, the essence of aché, may you always protect and watch over us all.

Embracing My Sacred Inner Soul

Introduction

I did not know I was born into a family that practiced Espiritismo and Santería until I was grown and had children of my own. When I was growing up, my mother, father, and grandmother kept their prayers to their ancestors and the worship of their divinities behind doors that were closed to me. Still, images of Santería divinities filled our home. My mother prayed to the orishas, the gods and goddesses of creation, almost every day. My father called upon the powers of the spirits when my mother fell ill. And my grandmother, my abuela, maintained one of the most beautiful altars to an orisha I have ever seen.

I was not the first child to come from a family who hid their worship of African gods and goddesses and practiced their religion in secret. The Moreno family was one of thousands, all born from generations of Africans in the Americas who hid their beliefs behind the images of their captors’ religion, masking their orishas with the faces of their enslavers’ saints. And for this reason, my ancestors’ religion came to be known as Santería, the Way of the Saints.

The orishas first came to Cuba on the ships of slaves, transported by means of the transatlantic slave trade of the early sixteenth century. On those ships were the Yoruba people, a peaceful, gentle tribe of West Africans who trace their origins back to A.D. 1000 to the sacred city of Ile Ife, today located in Nigeria. Though the enslavement of Africans was formally abolished by the Spaniards in Cuba in 1886 and in Puerto Rico in 1873, the Spanish government turned a blind eye to those who continued to smuggle African slaves into their colonies well into the late eighteen hundreds. Over a period of four centuries, more than fifteen million Africans of varied ethnic groups were brought as chattel slaves to the Americas, and they would leave their imprint on the New World.

As Africans in Cuba carefully guarded their ancient religious rituals, they wisely kept their beliefs hidden from the eyes of their plantation owners. Masking their divinities, their orishas, behind the images of the Catholic saints of their Spanish oppressors, the devoted were able to continue practicing their Yoruba beliefs. This process of camouflage allowed the ancient orishas, born in the sacred city of Ile Ife, West Africa, to survive wherever Yoruba ethnic groups were taken. In Brazil, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the United States, Santo Domingo, Trinidad, and Tobago, Africans evolved similar ways of protecting the orishas. Throughout the Caribbean and the Americas, Africans culturally re-created their belief systems, grounding them in the traditions of their tribal heritages. In this way, ancestor worship and the age-old tales of the African divinities were preserved in the memories of their descendants, secretly passed down through more than four hundred years of enslavement.

Each geographic community fostered branches of the orisha tradition; the branches share m

any commonalities. Africans in Brazil developed Candomblé; in Trinidad and Tobago they created Shangó; in Haiti and in the southern states of the United States they created Vodun; in Jamaica, Kumina; and in Cuba, Santería.

After more than four centuries of protection by African descendants in Cuba, the Santería community now spans the globe, with millions of practitioners celebrating this religion worldwide. Historically a religion practiced only by Africans and their descendants, Santería is now practiced by people of all racial and cultural communities, all who acknowledge the contributions and struggles of our ancestors. They honor the spirits of our ancestors, and are guided by them through the practice of Espiritismo, ancestor worship. They recognize a divine connection between our secular and sacred worlds, embracing both with the power of the orishas. They seek to find a balance with the forces in nature, known as aché. They learn how to channel these forces in a way that fosters spiritual growth, good health, prosperity, and the unification of both our family and our community.

I was initiated into the Lucumí religion, popularly known as Santería, in 1981 in Havana, Cuba. In search of a religion that reflected my racial and cultural heritage, I was led to Cuba by the spirits of my ancestors. During my first visit two years earlier, I had been introduced by my friend Javier Colón to two sages who would later become my godparents and guides in learning the philosophy and practices of the Santería religion. Upon my return to Cuba, their teachings opened my mind and soul to the sacred Yoruba-based knowledge of West Africa that had been preserved in the religion of Santería. My godfather, Oluwo Elpidio Cárdenas, and his wife and my godmother, Iyalorisha Zenaida Rodríguez, are both elder initiates in Santería, who nurtured me on a path that ultimately led to my full initiation into the religion.

Through my godparents’ guidance, I have connected to loved ones who reside in the spirit world. I have learned to live in balance with the forces of nature that surround me. And I have come to cherish my spiritual role as a godmother and priestess, teaching the traditions and rituals of Santería to a new generation of initiates.

In my roles of godmother, priestess, and scholar, I have occasion to address culturally diverse public forums on the subject of Santería. It is interesting to note how fascinated people are with Santería, and how much of this religion is already known through films, television, and the press. Although a glut of misinformation exists, audiences, filled with many people who are not of African descent, hold great curiosity about Santería. The history of the orishas in Africa, their journey to the Americas, and Santería similarities to other faiths all present intriguing questions.

I share my story with you in the desire to answer some of these questions, and with the hope that my experiences will help others who are in search of their own spirituality. I hope that the healing rituals of Santería, which are positive influences in my life and in the lives of millions the world over, will be better understood. I have recorded my search for a religion that would answer my spiritual needs. And I share my journey so as to correct the misleading information and derogatory views about Santería that are still held by many.

In the pages that follow, you will join me on my journey from darkness into light. And along the way, you will learn that Santería espouses beliefs and practices common to all religions that honor the divine essence of nature. It is for this reason that the philosophical principles and basic practices of Santería presented in this book may seem familiar. It is my belief that each religion creates a different path toward achieving the same goals: to be embraced and healed by the divine creator, who invites us to cherish our sacred souls.

Native American religions worship every aspect of nature, and their affirmation that we live on sacred Mother Earth is similar to Santería’s belief that all aspects of nature are divine. Asian religions identify the energy force, or qi, as well as the principle of yin-yang—our equivalent of aché and the positive and negative balance embodied in the orisha Ellegua. In Judaism, practitioners sacrifice and cleanse with animals as we do, and they also burn candles to create a spiritually charged environment during rituals. I always make these comparisons between other religions and my own, because they show we are not so different as we may appear to be.

I am often questioned about my decision to become an initiate of Santería. Because so few open forums exist to discuss our individual journeys, these discussions sometimes become sessions of soul-wrenching testimony. People who are traveling on a spiritual quest want to share their journeys; they want to feel connected to others who are on the same path. In almost every question, there is an underlying desire to know if Santería is a positive religion.

Afraid of being labeled “devil worshipers” or thought of as members of a cult, people who are drawn to Santería often continue to hide their beliefs. Many have stopped their explorations due to the negative images portrayed in the media and the fear of being ostracized by their Christian friends and families.

I am continuously asked why I was initiated into a religion that has been misrepresented and maligned by “mainstream” religions, Hollywood, and the mass media. Friends and acquaintances of African origin still influenced by negative views of Santería approach me cautiously, out of fear of my casting a brujo, a spell, on them. While they admire my cultural pride in my Afro–Puerto Rican heritage and my courage in defying popular misconceptions about Santería, somewhere deep in their hearts it seems they doubt the benign beauty of their own sacred traditions.

We generally accept that there is a divine, invisible intelligence at work on our behalf. We sense it. Santería provides the means to live in the sacred moment and benefit from divine energy. Rather than viewing our premonitions, dreams, and sacred moments as extraordinary, Santería teaches us that we are protected by our guardian angels and orishas, who make the extraordinary seem natural. In illuminating the role of the sacred Santería divinities, my godmother, Zenaida, explained: “No one knows how water gets into the coconut. Yet we know it is there. Accept that you have an inner spirit that is the voice of the Almighty who will guide and protect you.”

Santería is a way of life that reconciles the divine knowledge of the spirit world with secular knowledge. It is a coming together of the invisible and visible worlds, giving us the means for heeding our inner spirit. Like other religious systems, Santería functions through the faith of each practitioner. All I ask is that you open your mind and heart and allow your inner spirit guides to speak and blossom within you.

There are many spiritual paths that can be taken; Santería is only one of them. I have had the opportunity to participate in other belief systems. While they did not answer my needs, I have learned that spirituality transcends all religious faiths. To respect the sacred essence we carry is to respect the divine within each of us. For me, Santería affirms that every one of us is holy, and we are all part of the sacred universe that reflects the goddesses and gods who made us in their image.

Welcome to my world.

The orisha Olodumare, the Supreme God, originally lived in the lower part of heaven, overlooking endless stretches of water. One day, Olodumare decided to create Earth, and sent an emissary, the orisha Obatalá, to perform this task. Olodumare gave Obatalá the materials he needed to create the world: a small bag of loose earth, a gold chain, and a five-toed hen.

Obatalá was instructed to use the chain to descend from heaven. When he reached the last link, he piled the loose earth on top of the water. Next, he placed the hen on the pile of earth, and ordered her to scatter the earth with her toes across the surface of the water.

When this was finished, Obatalá climbed the chain to heaven to report his success to Olodumare. Olodumare then sent his trusted assistant, the chameleon, to verify that the earth was dry. When his helper had assured him that the Earth was solid, Olodumare named Earth “Ile Ife,” the sacred house.

Before he retired to the uppermost level of heaven, Olodumare decided to distribute his sacred powers—aché. He united Obatalá, the

orisha of creation, and Yemayá, the orisha of the ocean, who gave birth to a pantheon of orishas, each possessing a share of Olodumare’s sacred power. At last, the divine power of Olodumare was dispersed. Then one day, Olodumare called them all from Earth to heaven and gave Obatalá the sacred power to create human life. Obatalá returned to Earth and created our ancestors, endowing them with his own divine power. We are all descendants from the first people of the sacred city of Ile Ife; we are all children of Olodumare, the sacred orisha who created the world.

It was ten o’clock on Monday morning, August 25, 1997, when I arrived at the home of Doña Rosa, a Santería priestess of Yemayá. A short, wiry woman the color of sweet chocolate syrup, Doña Rosa was dressed in blue-and-white gingham in honor of her patron, Orisha Yemayá. She often lent her home to my godmother for initiation ceremonies, since her five-room, street-level apartment was large, had a small inside patio, and was centrally located in Havana, Cuba.

Doña Rosa greeted me with a warm embrace and then led me into the kitchen to await instructions from my godmother, my madrina, Zenaida, who was in a room off the kitchen, hidden by a white curtain, finalizing preparations for the ceremony that was about to begin. My madrina was planning to initiate a young Puerto Rican ritual drummer, omo añya, Paco Fuentes, into the Santería religion. He was to receive the aché of his patron, Orisha Shangó. Today was the asiento, the ritual that would ceremoniously place the aché of Shangó on the head of the new initiate.

Doña Rosa asked that I sit on a high wooden stool to await the portion of the ceremony in which I would participate. She offered me a glass of water and said, “My daughter, it is only ten o’clock in the morning and the heat is already close to ninety degrees.” Momentarily cooled by the water, I waited patiently for the ceremony to begin. The apartment was swarming with activity as the priestesses, the santeras, iyalorishas, prepared lunch. I tried to relax in the midst of the mounting excitement as santeras and santeros, babalorishas, the priests, hurried about collecting dishes, placing the sacrificial animals on the patio, and arranging the plants that would be used in the ceremony.

The Altar of My Soul

The Altar of My Soul