- Home

- Marta Moreno Vega

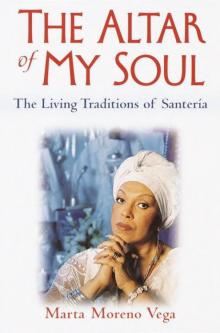

The Altar of My Soul Page 5

The Altar of My Soul Read online

Page 5

To lessen the troubles that awaited him, the babalawo advised Obatalá that he should take three changes of white clothing. It was most important, the babalawo told Obatalá, that he not lose his temper, for if he did, his life would not be spared. Heeding the advice of the diviner, Obatalá took three sets of clothing on his travels and vowed to stay calm.

Along the way, he met Ellegua, who was disguised as a poor peasant. When Ellegua asked Obatalá for help carrying a barrel filled with red palm oil, Obatalá willingly consented. Ellegua, playing his usual tricks, spilled palm oil on Obatalá’s clothes. He did so three times over. Each time, Obatalá calmly went to the nearest river, washed his clothes, and changed into clean ones.

Heeding the words of the diviner, he did not lose his patience. Ellegua was unable to shake Obatalá’s calm, and Obatalá was permitted to continue his journey with the knowledge that power resides in a cool head. He did not let the antics of Ellegua change his plans.

In a Cuban kitchen, many years and many miles away, the gentle hand of Doña Rosa on my shoulder woke me from my semidream state. Doña Rosa reminded me very much of my grandmother. She dressed like my abuela and wore her hair in the same way, and the warm color of her skin was like my grandmother’s. Both of them were much like the millions of African women who once toiled on plantations throughout the Americas. Like my grandmother, Doña Rosa was careful with her words because they carried not only aché, but the sacred spirit of the ancestral mothers. She selected her words as if she were choosing precious diamonds that would be handed down for generations to those who would treasure and value them forever.

As I sat waiting to be called into the initiation ceremony, Doña Rosa’s words again poured over me like a waterfall of cool, sparkling water. I needed to be reminded to let go of my fear of the unknown. I settled down and let my nervousness fade away, for she had made me understand that growth is a process of discovery. It is about releasing fear, taking risks, and above all letting divine intelligence fill us with creative inspiration, flowing unhindered.

In high school, I sometimes felt that I was wasting my time pursuing an arts career. It felt as if invisible barriers were constantly placed in my way. My guidance counselor advised me against entering the field of fashion design because she felt that it was exclusionary and racist. I considered a career in commercial art and again my adviser said that doors would be closed because of the color of my skin. Then I decided that I wanted to become an arts teacher. Once again my counselor suggested I think about another career possibility. When I graduated from the High School of Music and Art in 1959, my decision was to pursue a career in art education. I would not be stopped.

Tomás and I graduated from the High School of Music and Art at the same time. Our friendship had deepened by our sophomore year in high school, and we became inseparable. With the assistance of our high school counselor, we were both accepted by New York University’s art education department in the same year, and we both enrolled against our parents’ wishes.

Tom’s mother, an employee in a clothing sweatshop, encouraged him to leave school to take a job in the factory. She was the sole supporter of her mother and three children and desperately needed financial assistance. Determined not to accept public assistance, Tom’s mother worked fourteen-hour shifts daily. Food was so scarce in his home that Mrs. Vega placed a padlock on the refrigerator. Understanding the need to contribute financially to his family, Tom held three part-time jobs while attending school full-time. He was so anxious and exhausted that sometimes he would fall asleep in class. Nevertheless, he made the commitment to finish his education, although his mother unwittingly undermined his goals. With the help of a partial scholarship, student loans, and the money he earned, Tom continued in school.

Convinced that there was no future in the arts, my parents kept insisting that I quit school and seek a vocational education. Still, they stood by me, struggling to scrape together the money that my student loan and partial scholarship did not cover. To help meet my university expenses, I found a part-time job as a typist in a caviar factory near the college.

Tom and I provided our own motivational support network. We realized that our parents wanted the best for us, but that their vision was limited by the barriers they had faced during their own youths. Although we were confronted by racist comments in high school and at the university, it was clear to us that an education would be our path to opportunities that our families had never had.

On campus, we saw very few black or Latino students. We were the only Puerto Ricans in our department, and there was only one African American student, who eventually dropped out. Tom and I were living through our own civil rights struggle in New York City. The news reports of the civil rights fervor in the South was beginning to sweep the nation, and it empowered us, for this was our battle as well. One of our art professors was the distinguished African American artist Hale Woodruff, who quickly became our mentor and friend. He became the adult voice of encouragement, helping us over the aesthetic and social hurdles we faced in the department.

If Tom and I considered the students at the High School of Music and Art to be rich in comparison to our economic situation, the students at New York University all seemed to be millionaires. With the other students in the art department, I felt a kind of invisible barrier. Racial, cultural, and social differences influenced their perceptions, values, and understanding. And it became increasingly apparent that most of the students in my classes had never heard of El Barrio, had never been in a tenement building, and would never have met a Puerto Rican if Tom and I had not been in their classes.

It made me laugh to see their designer sneakers hand-smudged so they wouldn’t look new, while my ordinary shoes were dirty because they were truly worn. Their designer jeans were hand-torn to achieve a “hip,” lived-in look, while the threads in my jeans were giving up from constant wear.

I was appalled by the arrogance and wastefulness of privilege. Many students would leave half-finished tubes of paint lying about the art studio. They would throw away almost new paint palettes and canvases in fits of artistic temperament. Since we were barely able to purchase the required art supplies for class, these pretentious acts worked to Tom’s and my advantage. We waited until everyone had left, then rummaged through the garbage to salvage items we needed. Often Professor Woodruff would gather supplies left in his other art classes and save them for us.

At first, we felt uncomfortable and at the margins of the department’s activities. As we made friends with some other students who were poor and white, we became part of a small group of “starving hip art students”who discussed the role of the arts as a means for social and economic revolution. We envisioned ourselves as serious artists and spent endless hours talking about how we would solve esoteric problems.

As a blossoming art student, I had begun to experience life outside El Barrio. Tom and I would hang out in the Lower East Side or the East Village, roaming around with friends, partaking of the fringe artistic atmosphere developing in the area. I soon realized that the culture I grew up with and took for granted was not only very different from that of other students, but completely unknown to them. I was unfamiliar with the Eurocentric arts movement of downtown New York, which was as elitist as it was avant-garde, and the Caribbean images, colors, and textures that nurtured my youth were foreign to my classmates. My paintings illustrated the clashing complexity of colorful patterns that recalled the altars of my abuela and the vibrancy of my home.

Why paint apples and oranges, or cartoonlike images of Campbells soup, Marilyn Monroe, and Jackie Kennedy, I thought, when the Madama, the African woman, or El Kongo, the African man, surrounded by mangoes, plantains, pineapples, and other fruits my grandmother placed before the statues were ideal subjects? The colors of the objects and symbols that surrounded me daily were the images that became the focus of my paintings. The foods of the spirits placed on straw mats, the fiery defiant dance of the Gypsy swirling in reds and oranges, and ma

ny other images were my declaration that life in East Harlem also had artistic meaning. I made the conscious decision that my cultural heritage, which was ignored in my art history classes, would be the spring from which my creativity would flow.

Although my teachers were tolerant of my aesthetic vision, their puzzled faces made it clear to me that they did not really understand or appreciate my work. The instructors and students often asked for explanations of the images. I knew a mango was a tropical fruit and the Gypsy was from Spain, but when I responded to their questions about the content of my paintings, I expressed feelings of pride and demonstrated my growing knowledge of Puerto Rican history. I explained that the images of the flamenco dancer spoke to the cultural influence of the Spaniards in Puerto Rico. The Madama and old Kongo were the symbols of enslaved men and women brought to the island, and the Indian chief represented the Taínos people, who had been decimated by Spanish conquest. Although my explanation was incomplete, it marked the beginning of my cultural studies.

By 1962, the year before our graduation from New York University, Tom and I had developed our own aesthetic cultural vision. Tom’s confidence in his artistic talent was extraordinary, and he lent me the courage to express my own vision. Painting scenes in his neighborhood at the last minute between his many jobs and his school schedule, Tom was beginning to sell his work to small galleries. My images culled from my abuela’s bóveda and my home had many echoes for him, and he convinced me that we did have an audience for our work. It did not matter that our work was often misunderstood; it was tantalizing and intriguing, and the instructors and other students often would create their own meanings. We were frequently criticized for our representative art forms, since the artistic trends supported abstract expressionist and minimalist art. After class we would laugh at the misinterpretations of our work until we finally figured out that their opinions did not matter; we were getting wonderful grades and were deepening our knowledge of our heritage.

Tom and I graduated as art education teachers in May 1963, and we started teaching in the public schools by September 1963. I taught at Manhattan’s P.S. 60, a junior high school located on Twelfth Street, and Tom taught near his home in the Baruch Projects on the Lower East Side. Having accomplished our educational goals, we turned our attention to the next phase of our lives. We were sitting by the fountain in Washington Square Park, proudly examining our graduation diplomas, when Tom asked me to marry him by casually inviting me to accompany him to city hall. Knowing his work schedule, I was surprised by his request because he had to be at work in another half hour. “What about your job?” I asked. He shyly responded, “I took time off so we could go get our marriage license.” In 1963, we had been together for eight years, and we believed we were finally ready to begin our lives together.

We wanted a civil ceremony at city hall since we were not members of any formal religion, and thought it was a good way to bypass an expensive wedding. With the payment of student loans looming in the near future, we had no money to waste on what we thought was a meaningless public event. Nevertheless, my mother insisted on a Catholic church ceremony. Much loved and pampered by my mother, Tom gave little resistance to her request. Sitting at the kitchen table, I saw his resolve melt as he said, “Mom is right. We will remember our marriage day for the rest of our lives. Let’s make it special.” My mother wanted to make certain that the neighborhood realized her daughter was a virgin. It was important for my mother to display my “Puerto Rican señorita” virtuousness by having me wed in a white dress. Although I continued to argue against a church ceremony, my parents refused to accept my decision. They reasoned that as baptized Catholics, we must have a Catholic wedding. It was clear to me, however, that they were more concerned about our gossipy neighbors than the blessings of the religious rite.

When we went to make the arrangements, I discovered that the church insisted that I first receive my official confirmation and that I attend classes to learn the rules of the Catholic religion.

A priest in gold spectacles, dressed in a long black robe, ushered me into the church basement where I joined others for the Catechism class. His flushed pink cheeks contrasted sharply against his pale bluish skin and white collar. The sterile, cold environment was made more depressing by the image of a bleeding Christ crucified on a cross mounted on the front wall. Father Fitzpatrick’s clear blue eyes, slight Irish accent, and unsmiling mouth made him appear like one of the many Catholic statues hanging in the church chapel.

In his monotonous voice, he carefully explained the precepts of the church, but once I began to learn the fundamental canon of the church, my initial interest quickly faded. I could not accept that my loved ones had been born with original sin. I did not understand why I had to confess my sins to a priest. It was difficult for me to believe that a man, or any one person, had the power to absolve me of a sin I did not commit. None of it made sense to me. But to appease my mother, I was married in the church. To please myself, I stopped going to Sunday mass.

Finally, after six weeks, on March 29, 1964, Tom and I were married in East Harlem at St. Lucy’s Church on East 104th Street. Shortly thereafter we moved to an apartment one block up from the church to be near my parents.

The first years of our marriage were wonderful. Tom and I decided to wait to have children in order to complete our graduate work at New York University. We decided to continue our studies in the field of higher education, eventually planning to become college professors. Our respective families were overjoyed at our accomplishments. They quickly forgot their opposition to our educational goals and celebrated how instrumental they had been in our achieving our professional objectives.

On reflection, I am glad I granted my mother’s wish to be married in the Catholic church. She had known at the time that she was ill and her weak heart could not sustain her much longer, but she hid it from us. Six months after my marriage, my mother died. Soon after her passing, we found letters she had written to each family member.

In my letter, she explained how she had asked the spirits to let her live to see me graduate, marry, and start my professional career. “My life has been blessed by the spirits,” she wrote. “They didn’t take me away from my children when I experienced my first heart attack. I asked to be spared and live to see my youngest child flower into womanhood. I have been given this blessed opportunity. The time has come for me to leave you. Do not cry or mourn, because I will always be with you.” And now, after many years, I do truly understand that my mother and other loved ones are, in fact, always with me.

In her letter to my father, my mother asked that he help keep the family together. She was the one who insisted the family get together for Sunday dinners. When we all left home to start our families, she would call us each day to make certain all was well. In her letter, it was clear she wanted him to take her place, but although he tried, he could not change the years of being the strong macho patriarch. Abuela had died in 1959 and my mother in 1964, leaving a large void in our family. In a short period of time we had lost two loved ones, and I was devastated. Feeling lost and in need of healing, I would get up early on Sundays to sit in church. I found sitting in the solitude of the chapel before mass spiritually comforting, and walking to church at six in the morning was so peaceful. The only people I saw walking in the shadows of dawn were elderly Italian and Puerto Rican women dressed in black on their way to church.

Those early Sunday mornings alone in the church seemed to satisfy my growing need for a connection beyond my everyday world. The altar, covered by intricately embroidered, luxurious cloths, reminded me of my abuela’s sacred room. The brilliant colors of the statues of the saints and the scent of burning incense created a familiar feeling that was soothing to my inner being, evoking thoughts of my mother and La Perpetuo Socorro. Memories of my abuela’s home also filled my thoughts as the flickering flames of candles and stained-glass windows reflected a rainbow of warmth.

Going to church early on Sundays became a weekly r

itual. Surrounded by the echoes of silence, the solitude and privacy was like being in the bosom of my abuela and mother. Sometimes I was the only person in the dark, nearly empty nave. Other times, if I was joined by two or three older women who piously knelt to recite the rosary, the church felt like a tomb. In their solemn black dresses, they knelt and prayed at each of the stations of the cross, and they often wept softly. Their devotion and sacrifice expressed a deep love that was coupled with sorrow. Respecting their devotion, I felt uneasy with what appeared to be a profound sadness engulfing them. My own reasons for attending church were very different.

I looked forward to my Sunday mornings of sacred solitude with joy. Each week, however, the sacred joy that filled me on Sundays disappeared too quickly. I could never understand why this feeling did not last past the chapel’s doors.

Both Tom and I continued to explore our career options after we completed graduate school in 1966. Tom decided to teach in a private elementary school, and I decided to continue teaching in the public schools. Our worlds were suddenly different. He was in an environment that valued education and prepared students to enroll in schools like the High School of Music and Art. I was working with students who could barely stay in school because of dysfunctional homes or the need to contribute to family income. My students were no longer children; they were becoming adults, dealing with grown-up problems. Many had to baby-sit so their parents could work. Others held part-time jobs after school to help at home.

I became pregnant with our first child, Sergio, in 1968. At the time, I was teaching in Washington Irving High School, then an all-girls school. For many students I was the first Puerto Rican teacher they had ever had. I became their mentor, guidance counselor, role model, and mother. Like my junior high school art teacher had done, I spoke with parents, encouraging them to allow their daughters to pursue their artistic goals. In my position I felt that I was making a difference. There were many times when I had to defend students who were the target of discrimination by an overwhelmingly insensitive portion of the European American faculty. Since I was frequently mistaken for a student, teachers would often be extremely rude when they spoke with me. One day I was even pulled out of the teachers’ lounge because one of the faculty members refused to believe that I could be a teacher.

The Altar of My Soul

The Altar of My Soul